Over the last few months, I have had the opportunity to complete an inquiry project of my choice while being exposed to many helpful tools available to support further research projects. My final refection will include: a quick overview of the tools I found the most useful, a review of my learning through blogging, a succinct synopsis of my research paper, and an acknowledgement for my peers who also taught me many relevant concepts to be incorporated into my classroom.

Tools

This course introduced me to many fabulous tools. The most relevant and frequently used tool for me was Zotero. With only a few classes left before our final project begins, this tool will support any referencing I need to use in the future. Matt Huculak, a Librarian from the University of Victoria, shared an amazing how-to video about Zotero. While the video is daunting at an hour long, using Zotero has changed my referencing life! Forgetting a reference accidentally is one of my biggest academic fears, so having a tool that supports my citations has made a world of a difference.

The second tool I interacted with regularly was Trello. Trello is an online project management tool. It allows the user to generate to-do lists with deadlines. It can be shared with others to support research projects. I like this tool because it keeps the larger project in view while breaking it down into smaller steps making it less overwhelming. I am hoping to use Trello with my project supervisor to make sure I am on track to complete my large final project on time.

Although this isn’t a specific tool but rather a skill, knowing where and how to credit one’s image sources, is very important. I didn’t know how to look for creative common images or that creative common images even existed. I will be able to use this skill for inserting images into my newsletters, adding images to my blog, or when downloading images for students.

Blog Learning

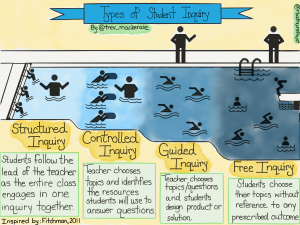

Overall, I felt like Kindergarten students’ fine motor skills have been decreasing, in my experience, since I started teaching Kindergarten in 2012. I wanted to learn how to increase fine motor skills in my classroom, what the experts were saying about current trends, and the pros and cons of technology in supporting or decreasing fine motor skills. The overarching theme in many of my previous posts was balance: a balance between spending time on touch screen technology and playing with traditional toys, a balance between printing with pencil and paper and using apps to support letter formation, and a balance between time spent with parents or caregivers while using touch screen devices and opportunities to use technology independently.

The Victoria State Government website, shared in an earlier post, offers many great activities to support fine motor growth. Many of these ideas can be offered in the classroom. The Letter School app was suggested in a research paper by C. Bulter, R. Pimenta, J. Tommerdahl, C. Fuchs, and P. Caçola (2019).(CITE) This app, along with others, was also suggested by Alision Stewert, an Occupational Therapist, to support printing practice in the classroom. I have been using this app in my classroom with one child to support their printing and fine motor skills. I have already seen a significant improvement in their fine motor skills. However, I would not agree that their improvement is solely because of this app. Like Lin L., Cherng R., and Chen Y. (2016) noted in their original research project, young children make more of an improvement when playing with traditional toys then when only using tablets. As an educator interested in fine motor skills, many of the toys and centre activities in my classroom involve a fine motor component, thus providing this student with ample fine motor skill improvement opportunities.

If I am going to use touch screen technology as one of many tools to support fine motor skills, I also wanted to examine styluses. In my opinion, there is no point in children using an app to support printing, if their finger is using swiping or dragging instead of holding a stylus using the proper pencil grip. I went down a deep rabbit hole learning about all sorts of different styluses and even when the first touch screen device was made. (I’ll give you a hint – it was not Apple’s iPad!) I did not know there were so many choices available. After speaking with Alison, I have ordered a few for my classroom that she suggested would be best to support children.

Again, understanding the overarching theme of balance, I learned that technology isn’t going away so it should not be excluded from the classroom. As educators, we need to be flexible, allowing children the opportunities to learn the skills they will need to be successful adults. Exposure to technology as a tool verses a toy will benefit children in their future whether is it used specifically for fine motor skills or for other educational purposes.

Research Paper

I really enjoyed my research topic. It was very hard to keep my topic narrow and only focus on one specific question in regard to young children’s fine motor skills. I wanted to know if Kindergarten aged children (ages 4- to 6-years old) actually had decreased fine motor skills. It turns out they do. One study from 1986, by Mathiowetz, Wiemer, and Federman, had tested children between the ages of 6 and 19 in order to have a set of norms that could be used to compare children and their abilities. In more current studies (Cohen et al., 2011; Gaul & Issartel, 2016; McQuiddy, Scheerer, Lavalley, McGrath, & Lin, 2015), hand and grip strength has significantly decreased in young children. Now that I have the research to back up my own observations, I can incorporate fine motor activities knowing that they are necessary.

Peer Learning

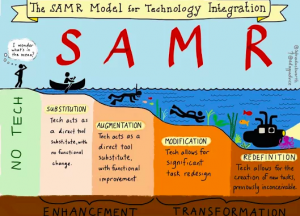

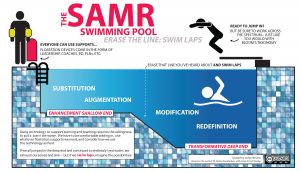

I was fortunate to be a part of an extraordinary learning pod. I learned so many things from this wonderful group of ladies that are relevant and practical to my every day classroom experiences. The collaboration between us was fruitful. Many of our weekly posts involved an app that we discovered through our research. We shared these apps and our experiences with them on a shared google doc for future reference. Sarahfromtheprairies reaffirmed my belief in home reading programs and the importance in parents spending quality time with their children reading. Tiny Island Blog provided me with the knowledge to support telehealth in schools. Although my school uses Tiny Eye, I didn’t really support the idea. My eyes have been opened to the benefits! Last but certainly not least, Laucoo’s views on technology made me re-think my own viewpoints. I use technology frequently throughout the day and examining my use of technology reminded me to make sure that the tech route was really the best way to instruct or use my time with my students. In some areas, I’ve reduced its use and in other areas, I have increased its use. Laucoo’s blog was a good reminder to check in with things I am using to make sure they are still applicable, relevant, and best practice. I sincerely thank all my pod members for the support they have given me during this learning journey.

In conclusion, this course provided me with lots of learning opportunities from many different sources. Specific goals aside, I think this was also a good experience to support the research required for my final paper. Going through the research process of a topic of my own choice, and finding relevant readings, experts, and tools, while under the guidance of a professor and within a short time frame gave me the tools needed to write my final paper. I will be able to apply these new research skills to my next inquiry project. A big thank you to my professor for being available, flexible, and willing to support me in my learning goals.

References:

Cohen, D., Voss, C., Taylor, M., Delextrat, A., Ogunleye, A., & Sandercock, G. (2011). Ten‐year secular changes in muscular fitness in English children. Acta Paediatrica, 100(10), e175–e177. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02318.x

Fine motor. (n.d.). Retrieved November 27, 2019, from https://www.education.vic.gov.au:443/childhood/professionals/learning/ecliteracy/emergentliteracy/Pages/finemoto.aspx

Gaul, D., & Issartel, J. (2016). Fine motor skill proficiency in typically developing children: On or off the maturation track? Human Movement Science, 46, 78–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humov.2015.12.011

LauCoo Learning. (n.d.). Retrieved November 27, 2019, from https://laucoo.opened.ca/

LetterSchool: Learn to read & write. (n.d.). Retrieved October 12, 2019, from LetterSchool website: https://www.letterschool.org

Mathiowetz, V., Wiemer, D. M., & Federman, S. M. (1986). Grip and Pinch Strength: Norms for 6- to 19-Year-Olds. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 40(10), 705–711. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.40.10.705

McQuiddy, V. A., Scheerer, C. R., Lavalley, R., McGrath, T., & Lin, L. (2015). Normative Values for Grip and Pinch Strength for 6- to 19-Year-Olds. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 96(9), 1627–1633. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2015.03.018

Sarahfromtheprairies. (n.d.). Retrieved November 27, 2019, from https://sarahfromtheprairies.opened.ca/

Tiny Island Learning – EDCI 567 – Fall 2019. (n.d.). Retrieved November 27, 2019, from https://edci567-fall19-tinyisland.opened.ca/

Trello. (n.d.). Retrieved November 27, 2019, from https://trello.com

Zotero | Your personal research assistant. (n.d.). Retrieved November 27, 2019, from https://www.zotero.org/

Zotero workshop by Matt Huculak of UVic Libraries—YouTube. (n.d.). Retrieved November 27, 2019, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qvPvBmeUduA&list=WL&index=2&t=2420s

Recent Comments